HinduismEdit

See also: Hindu views on evolution, List of numbers in Hindu scriptures, Hindu cosmology, Hindu units of time, Indian astronomy, Hindu calendar, Indian mathematics, and List of Indian inventions and discoveries

In Hinduism, the dividing line between objective sciences and spiritual knowledge (adhyatma vidya) is a linguistic paradox.[135] Hindu scholastic activities and ancient Indian scientific advancements were so interconnected that many Hindu scriptures are also ancient scientific manuals and vice versa. In 1835, English was made the primary language for teaching in higher education in India, exposing Hindu scholars to Western secular ideas; this started a renaissance regarding religious and philosophical thought.[136] Hindu sages maintained that logical argument and rational proof using Nyaya is the way to obtain correct knowledge.[135] The scientific level of understanding focuses on how things work and from where they originate, while Hinduism strives to understand the ultimate purposes for the existence of living things.[136] To obtain and broaden the knowledge of the world for spiritual perfection, many refer to the Bhāgavata for guidance because it draws upon a scientific and theological dialogue.[137] Hinduism offers methods to correct and transform itself in course of time. For instance, Hindu views on the development of life include a range of viewpoints in regards to evolution, creationism, and the origin of life within the traditions of Hinduism. For instance, it has been suggested that Wallace-Darwininan evolutionary thought was a part of Hindu thought centuries before modern times.[138] The Shankara and the Sāmkhya did not have a problem with the theory of evolution, but instead, argued about the existence of God and what happened after death. These two distinct groups argued among each other’s philosophies because of their sacred texts, not the idea of evolution.[139] With the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, many Hindus were eager to connect their scriptures to Darwinism, finding similarities between Brahma’s creation, Vishnu’s incarnations, and evolution theories.[136]

Samkhya, the oldest school of Hindu philosophy prescribes a particular method to analyze knowledge. According to Samkhya, all knowledge is possible through three means of valid knowledge[140][141] –

- Pratyakṣa or Dṛṣṭam – direct sense perception,

- Anumāna – logical inference and

- Śabda or Āptavacana – verbal testimony.

Nyaya, the Hindu school of logic, accepts all these 3 means and in addition accepts one more – Upamāna (comparison).

The accounts of the emergence of life within the universe vary in description, but classically the deity called Brahma, from a Trimurti of three deities also including Vishnu and Shiva, is described as performing the act of ‘creation’, or more specifically of ‘propagating life within the universe’ with the other two deities being responsible for ‘preservation’ and ‘destruction’ (of the universe) respectively.[142] In this respect some Hindu schools do not treat the scriptural creation myth literally and often the creation stories themselves do not go into specific detail, thus leaving open the possibility of incorporating at least some theories in support of evolution. Some Hindus find support for, or foreshadowing of evolutionary ideas in scriptures, namely the Vedas.[143]

The incarnations of Vishnu (Dashavatara) is almost identical to the scientific explanation of the sequence of biological evolution of man and animals.[144][145][146][147] The sequence of avatars starts from an aquatic organism (Matsya), to an amphibian (Kurma), to a land-animal (Varaha), to a humanoid (Narasimha), to a dwarf human (Vamana), to 5 forms of well developed human beings (Parashurama, Rama, Balarama/Buddha, Krishna, Kalki) who showcase an increasing form of complexity (Axe-man, King, Plougher/Sage, wise Statesman, mighty Warrior).[144][147] In fact, many Hindu gods are represented with features of animals as well as those of humans, leading many Hindus to easily accept evolutionary links between animals and humans.[136] In India, the home country of Hindus, educated Hindus widely accept the theory of biological evolution. In a survey of 909 people, 77% of respondents in India agreed with Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, and 85 per cent of God-believing people said they believe in evolution as well.[148][149]

As per Vedas, another explanation for the creation is based on the five elements: earth, water, fire, air and aether. The Hindu religion traces its beginnings to the sacred Vedas. Everything that is established in the Hindu faith such as the gods and goddesses, doctrines, chants, spiritual insights, etc. flow from the poetry of Vedic hymns. The Vedas offer an honor to the sun and moon, water and wind, and to the order in Nature that is universal. This naturalism is the beginning of what further becomes the connection between Hinduism and science.[150]

IslamEdit

Main article: Islam and science

See also: Science in the medieval Islamic world

From an Islamic standpoint, science, the study of nature, is considered to be linked to the concept of Tawhid (the Oneness of God), as are all other branches of knowledge.[151] In Islam, nature is not seen as a separate entity, but rather as an integral part of Islam’s holistic outlook on God, humanity, and the world. The Islamic view of science and nature is continuous with that of religion and God. This link implies a sacred aspect to the pursuit of scientific knowledge by Muslims, as nature itself is viewed in the Qur’an as a compilation of signs pointing to the Divine.[152] It was with this understanding that science was studied and understood in Islamic civilizations, specifically during the eighth to sixteenth centuries, prior to the colonization of the Muslim world.[153] Robert Briffault, in The Making of Humanity, asserts that the very existence of science, as it is understood in the modern sense, is rooted in the scientific thought and knowledge that emerged in Islamic civilizations during this time.[154] Ibn al-Haytham, an Arab[155] Muslim,[156][157][158] was an early proponent of the concept that a hypothesis must be proved by experiments based on confirmable procedures or mathematical evidence—hence understanding the scientific method 200 years before Renaissance scientists.[159][2][160][161][162] Ibn al-Haytham described his theology:

I constantly sought knowledge and truth, and it became my belief that for gaining access to the effulgence and closeness to God, there is no better way than that of searching for truth and knowledge.[163]

With the decline of Islamic Civilizations in the late Middle Ages and the rise of Europe, the Islamic scientific tradition shifted into a new period. Institutions that had existed for centuries in the Muslim world looked to the new scientific institutions of European powers.[citation needed] This changed the practice of science in the Muslim world, as Islamic scientists had to confront the western approach to scientific learning, which was based on a different philosophy of nature.[151] From the time of this initial upheaval of the Islamic scientific tradition to the present day, Muslim scientists and scholars have developed a spectrum of viewpoints on the place of scientific learning within the context of Islam, none of which are universally accepted or practiced.[164] However, most maintain the view that the acquisition of knowledge and scientific pursuit in general is not in disaccord with Islamic thought and religious belief.[151][164]

AhmadiyyaEdit

Further information: Ahmadiyya views on evolution

The Ahmadiyya movement emphasize that there is no contradiction between Islam and science.[citation needed] For example, Ahmadi Muslims universally accept in principle the process of evolution, albeit divinely guided, and actively promote it. Over the course of several decades the movement has issued various publications in support of the scientific concepts behind the process of evolution, and frequently engages in promoting how religious scriptures, such as the Qur’an, supports the concept.[165] For general purposes, the second Khalifa of the community, Mirza Basheer-ud-Din Mahmood Ahmad says:

The Holy Quran directs attention towards science, time and again, rather than evoking prejudice against it. The Quran has never advised against studying science, lest the reader should become a non-believer; because it has no such fear or concern. The Holy Quran is not worried that if people will learn the laws of nature its spell will break. The Quran has not prevented people from science, rather it states, “Say, ‘Reflect on what is happening in the heavens and the earth.'” (Al Younus)[166]

JainismEdit

Main article: Jainism and non-creationism

Jainism does not support belief in a creator deity. According to Jain doctrine, the universe and its constituents – soul, matter, space, time, and principles of motion have always existed (a static universe similar to that of Epicureanism and steady state cosmological model). All the constituents and actions are governed by universal natural laws. It is not possible to create matter out of nothing and hence the sum total of matter in the universe remains the same (similar to law of conservation of mass). Similarly, the soul of each living being is unique and uncreated and has existed since beginningless time.[a][167]

The Jain theory of causation holds that a cause and its effect are always identical in nature and hence a conscious and immaterial entity like God cannot create a material entity like the universe. Furthermore, according to the Jain concept of divinity, any soul who destroys its karmas and desires, achieves liberation. A soul who destroys all its passions and desires has no desire to interfere in the working of the universe. Moral rewards and sufferings are not the work of a divine being, but a result of an innate moral order in the cosmos; a self-regulating mechanism whereby the individual reaps the fruits of his own actions through the workings of the karmas.

Through the ages, Jain philosophers have adamantly rejected and opposed the concept of creator and omnipotent God and this has resulted in Jainism being labeled as nastika darsana or atheist philosophy by the rival religious philosophies. The theme of non-creationism and absence of omnipotent God and divine grace runs strongly in all the philosophical dimensions of Jainism, including its cosmology, karma, moksa and its moral code of conduct. Jainism asserts a religious and virtuous life is possible without the idea of a creator god.[168]

Perspectives from the scientific communityEdit

HistoryEdit

Further information: List of Jewish scientists and philosophers, List of Christian thinkers in science, List of Muslim scientists, and List of atheists (science and technology)

In the 17th century, founders of the Royal Society largely held conventional and orthodox religious views, and a number of them were prominent Churchmen.[169] While theological issues that had the potential to be divisive were typically excluded from formal discussions of the early Society, many of its fellows nonetheless believed that their scientific activities provided support for traditional religious belief.[170] Clerical involvement in the Royal Society remained high until the mid-nineteenth century, when science became more professionalised.[171]

Albert Einstein supported the compatibility of some interpretations of religion with science. In “Science, Philosophy and Religion, A Symposium” published by the Conference on Science, Philosophy and Religion in Their Relation to the Democratic Way of Life, Inc., New York in 1941, Einstein stated:

Accordingly, a religious person is devout in the sense that he has no doubt of the significance and loftiness of those superpersonal objects and goals which neither require nor are capable of rational foundation. They exist with the same necessity and matter-of-factness as he himself. In this sense religion is the age-old endeavor of mankind to become clearly and completely conscious of these values and goals and constantly to strengthen and extend their effect. If one conceives of religion and science according to these definitions then a conflict between them appears impossible. For science can only ascertain what is, but not what should be, and outside of its domain value judgments of all kinds remain necessary. Religion, on the other hand, deals only with evaluations of human thought and action: it cannot justifiably speak of facts and relationships between facts. According to this interpretation the well-known conflicts between religion and science in the past must all be ascribed to a misapprehension of the situation which has been described.[172]

Einstein thus expresses views of ethical non-naturalism (contrasted to ethical naturalism).

Prominent modern scientists who are atheists include evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and Nobel Prize–winning physicist Stephen Weinberg. Prominent scientists advocating religious belief include Nobel Prize–winning physicist and United Church of Christ member Charles Townes, evangelical Christian and past head of the Human Genome Project Francis Collins, and climatologist John T. Houghton.[65]

Studies on scientists’ beliefsEdit

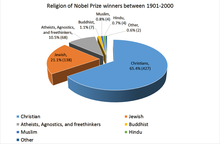

Distribution of Nobel Prizes by religion between 1901–2000.[173]

In 1916, 1,000 leading American scientists were randomly chosen from American Men of Science and 42% believed God existed, 42% disbelieved, and 17% had doubts/did not know; however when the study was replicated 80 years later using American Men and Women of Science in 1996, results were very much the same with 39% believing God exists, 45% disbelieved, and 15% had doubts/did not know.[65][174] In the same 1996 survey, scientists in the fields of biology, mathematics, and physics/astronomy, belief in a god that is “in intellectual and affective communication with humankind” was most popular among mathematicians (about 45%) and least popular among physicists (about 22%). In total, in terms of belief toward a personal god and personal immortality, about 60% of United States scientists in these fields expressed either disbelief or agnosticism and about 40% expressed belief.[174] This compared with 58% in 1914 and 67% in 1933.[citation needed]

A survey conducted between 2005 and 2007 by Elaine Howard Ecklund of University at Buffalo, The State University of New York of 1,646 natural and social science professors at 21 US research universities found that, in terms of belief in God or a higher power, more than 60% expressed either disbelief or agnosticism and more than 30% expressed belief. More specifically, nearly 34% answered “I do not believe in God” and about 30% answered “I do not know if there is a God and there is no way to find out.”[175] In the same study, 28% said they believed in God and 8% believed in a higher power that was not God.[176]Ecklund stated that scientists were often able to consider themselves spiritual without religion or belief in god.[177] Ecklund and Scheitle concluded, from their study, that the individuals from non-religious backgrounds disproportionately had self-selected into scientific professions and that the assumption that becoming a scientist necessarily leads to loss of religion is untenable since the study did not strongly support the idea that scientists had dropped religious identities due to their scientific training.[178] Instead, factors such as upbringing, age, and family size were significant influences on religious identification since those who had religious upbringing were more likely to be religious and those who had a non-religious upbringing were more likely to not be religious.[175][178][179] The authors also found little difference in religiosity between social and natural scientists.[179]

Since 1901–2013, 22% of all Nobel prizes have been awarded to Jews despite them being less than 1% of the world population.[180]

Between 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religion. Most (65%) have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference. Specifically on the science related prizes, Christians have won a total of 73% of all the Chemistry, 65% in Physics, 62% in Medicine, and 54% in all Economics awards.[173] Jews have won 17% of the prizes in Chemistry, 26% in Medicine, and 23% in Physics.[173] Atheists, Agnostics, and Freethinkers have won 7% of the prizes in Chemistry, 9% in Medicine, and 5% in Physics.[173] Muslims have won 13 prizes (three were in scientific category).

Many studies have been conducted in the United States and have generally found that scientists are less likely to believe in God than are the rest of the population. Precise definitions and statistics vary, with some studies concluding that about 1⁄3 of scientists in the U.S. 1⁄3 are atheists, 1⁄3 agnostic, and 1⁄3have some belief in God (although some might be deistic, for example).[65][174][181] This is in contrast to the more than roughly 3⁄4 of the general population that believe in some God in the United States. Other studies on scientific organizations like the AAAS show that 51% of their scientists believe in either God or a higher power and 48% having no religion.[182] Belief also varies slightly by field. Two surveys on physicists, geoscientists, biologists, mathematicians, and chemists have noted that, from those specializing in these fields, physicists had lowest percentage of belief in God (29%) while chemists had highest (41%).[174][183] Other studies show that among members of the National Academy of Sciences, concerning the existence of a personal god who answers prayer, 7% expressed belief, 72% expressed disbelief, and 21% were agnostic,[184] however Eugenie Scott argued that there are methodological issues in the study, including ambiguity in the questions. A study with simplified wording to include impersonal or non-interventionist ideas of God concluded that 40% of leading scientists in the US scientists believe in a god.[185]

In terms of perceptions, most social and natural scientists from 21 American universities did not perceive conflict between science and religion, while 37% did. However, in the study, scientists who had experienced limited exposure to religion tended to perceive conflict.[40] In the same study they found that nearly one in five atheist scientists who are parents (17%) are part of religious congregations and have attended a religious service more than once in the past year. Some of the reasons for doing so are their scientific identity (wishing to expose their children to all sources of knowledge so they can make up their own minds), spousal influence, and desire for community.[186]

A 2009 report by the Pew Research Center found that members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) were “much less religious than the general public,” with 51% believing in some form of deity or higher power. Specifically, 33% of those polled believe in God, 18% believe in a universal spirit or higher power, and 41% did not believe in either God or a higher power.[187] 48% say they have a religious affiliation, equal to the number who say they are not affiliated with any religious tradition. 17% were atheists, 11% were agnostics, 20% were nothing in particular, 8% were Jewish, 10% were Catholic, 16% were Protestant, 4% were Evangelical, 10% were other religion. The survey also found younger scientists to be “substantially more likely than their older counterparts to say they believe in God”. Among the surveyed fields, chemists were the most likely to say they believe in God.[183]

Elaine Ecklund conducted a study from 2011 to 2014 involving the general US population, including rank and file scientists, in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). The study noted that 76% of the scientists identified with a religious tradition. 85% of evangelical scientists had not doubts about the existence of God, compared to 35% of the whole scientific population. In terms of religion and science, 85% of evangelical scientists saw no conflict (73% collaboration, 12% independence), while 75% of the whole scientific population saw no conflict (40% collaboration, 35% independence).[188]

Religious beliefs of US professors were examined using a nationally representative sample of more than 1,400 professors. They found that in the social sciences: 23% did not believe in God, 16% did not know if God existed, 43% believed God existed, and 16% believed in a higher power. Out of the natural sciences: 20% did not believe in God, 33% did not know if God existed, 44% believed God existed, and 4% believed in a higher power. Overall, out of the whole study: 10% were atheists, 13% were agnostic, 19% believe in a higher power, 4% believe in God some of the time, 17% had doubts but believed in God, 35% believed in God and had no doubts.[189]

Farr Curlin, a University of Chicago Instructor in Medicine and a member of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, noted in a study that doctors tend to be science-minded religious people. He helped author a study that “found that 76 percent of doctors believe in God and 59 percent believe in some sort of afterlife.” and “90 percent of doctors in the United States attend religious services at least occasionally, compared to 81 percent of all adults.” He reasoned, “The responsibility to care for those who are suffering and the rewards of helping those in need resonate throughout most religious traditions.”[190]

Physicians in the United States, by contrast, are much more religious than scientists, with 76% stating a belief in God.[190]

Public perceptions of scienceEdit

See also: Religiosity and education

Global studies which have pooled data on religion and science from 1981–2001, have noted that countries with high religiosity also have stronger faith in science, while less religious countries have more skepticism of the impact of science and technology.[191] The United States is noted there as distinctive because of greater faith in both God and scientific progress. Other research cites the National Science Foundation‘s finding that America has more favorable public attitudes towards science than Europe, Russia, and Japan despite differences in levels of religiosity in these cultures.[192]

A study conducted on adolescents from Christian schools in Northern Ireland, noted a positive relationship between attitudes towards Christianity and science once attitudes towards scientism and creationism were accounted for.[193]

A study on people from Sweden concludes that though the Swedes are among the most non-religious, paranormal beliefs are prevalent among both the young and adult populations. This is likely due to a loss of confidence in institutions such as the Church and Science.[194]

Concerning specific topics like creationism, it is not an exclusively American phenomenon. A poll on adult Europeans revealed that 40% believed in naturalistic evolution, 21% in theistic evolution, 20% in special creation, and 19% are undecided; with the highest concentrations of young earth creationists in Switzerland (21%), Austria (20%), Germany (18%).[195] Other countries such as Netherlands, Britain, and Australia have experienced growth in such views as well.[195]

According to a 2015 Pew Research Center Study on the public perceptions on science, people’s perceptions on conflict with science have more to do with their perceptions of other people’s beliefs than their own personal beliefs. For instance, the majority of people with a religious affiliation (68%) saw no conflict between their own personal religious beliefs and science while the majority of those without a religious affiliation (76%) perceived science and religion to be in conflict.[196] The study noted that people who are not affiliated with any religion, also known as “religiously unaffiliated”, often have supernatural beliefs and spiritual practices despite them not being affiliated with any religion[196][197][198]and also that that “just one-in-six religiously unaffiliated adults (16%) say their own religious beliefs conflict with science.”[196] Furthermore, the study observed, “The share of all adults who perceive a conflict between science and their own religious beliefs has declined somewhat in recent years, from 36% in 2009 to 30% in 2014. Among those who are affiliated with a religion, the share of people who say there is a conflict between science and their personal religious beliefs dropped from 41% to 34% during this period.”[196]

According to the 2012 Pew Research Center study on those without a religion,

The 2013 MIT Survey on Science, Religion and Origins examined the views of religious people in America on origins science topics like evolution, the Big Bang, and perceptions of conflicts between science and religion. It found that a large majority of religious people see no conflict between science and religion and only 11% of religious people belong to religions openly rejecting evolution. The fact that the gap between personal and official beliefs of their religions is so large suggests that part of the problem, might be defused by people learning more about their own religious doctrine and the science it endorses, thereby bridging this belief gap. The study concluded that “mainstream religion and mainstream science are neither attacking one another nor perceiving a conflict.” Furthermore, they note that this conciliatory view is shared by most leading science organizations such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).[199]

A study collecting data from 2011 to 2014 on the general public, with focus on evangelicals and evangelical scientists was done in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Even though evangelicals only make up 26% of the US population, the found that nearly 70 percent of all evangelical Christians do not view science and religion as being in conflict with each other (48% saw them a complementary and 21% saw them as independent) while 73% of the general US population saw no conflict as well.[188][200]

Other lines of research on perceptions of science among the American public conclude that most religious groups see no general epistemological conflict with science and they have no differences with nonreligious groups in the propensity of seeking out scientific knowledge, although there may be subtle epistemic or moral conflicts when scientists make counterclaims to religious tenets.[201][202] Findings from the Pew Center note similar findings and also note that the majority of Americans (80–90%) show strong support for scientific research, agree that science makes society and individual’s lives better, and 8 in 10 Americans would be happy if their children were to become scientists.[203]Even strict creationists tend to have very favorable views on science.[192]

According to a 2007 poll by the Pew Forum, “while large majorities of Americans respect science and scientists, they are not always willing to accept scientific findings that squarely contradict their religious beliefs.”[204] The Pew Forum states that specific factual disagreements are “not common today”, though 40% to 50% of Americans do not accept the evolution of humans and other living things, with the “strongest opposition” coming from evangelical Christians at 65% saying life did not evolve.[204] 51% of the population believes humans and other living things evolved: 26% through natural selection only, 21% somehow guided, 4% don’t know.[204] In the U.S., biological evolution is the only concrete example of conflict where a significant portion of the American public denies scientific consensus for religious reasons.[192][204] In terms of advanced industrialized nations, the United States is the most religious.[204]

A 2009 study from the Pew Research Center on Americans perceptions of science, showed a broad consensus that most Americans, including most religious Americans, hold scientific research and scientists themselves in high regard. The study showed that 84% Americans say they view science as having a mostly positive impact on society. Among those who attend religious services at least once a week, the number is roughly the same at 80%. Furthermore, 70% of U.S. adults think scientists contribute “a lot” to society.[205]

A 2011 study on a national sample of US college students examined whether these students viewed the science / religion relationship as reflecting primarily conflict, collaboration, or independence. The study concluded that the majority of undergraduates in both the natural and social sciences do not see conflict between science and religion. Another finding in the study was that it is more likely for students to move away from a conflict perspective to an independence or collaboration perspective than towards a conflict view.[206]

In the US, people who had no religious affiliation were no more likely than the religious population to have New Age beliefs and practices.